Why Play-Based Learning Works:

Neuroscience, Benefits, and Effectiveness

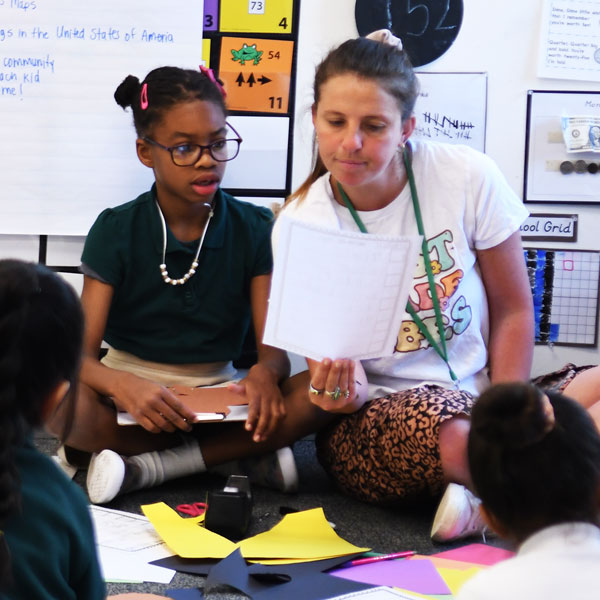

Play Isn’t Just Fun—It’s How Children Are Wired to Learn.

Improving outcomes and engagement doesn’t occur with more direct instruction hours or buying a new reading curriculum. Brain research and longitudinal studies prove that play-based learning delivers superior outcomes because it aligns with how children naturally learn.6,7,9,10 We set up children for success when we approach our educational practice in such a way that meets them where they are at developmentally.

The Neuroscience: How Young Brains Actually Learn

Children learn about the world through active engagement. Neuroscience tells us that young children’s brains cannot learn through direct instruction alone.1,7

Research Studies Show:1,3,9,10

- Active learning grows and strengthens neural pathways in ways that passive instruction does not

- Movement and manipulation activate multiple brain regions simultaneously

- Social interaction during learning enhances memory consolidation

- Positive emotions from engagement improve cognitive processing

The Executive Function Connection

Executive function skills predict future success better than IQ or family income.3,4,5,11

Play-based learning specifically develops the prefrontal cortex, responsible for:

Problem-solving and critical thinking

Emotional regulation and impulse control

Planning and decision-making

Research Evidence: Long-Term Impact

HighScope Perry Preschool Study8,11

Underserved children enrolled in the high-quality, play-based program showed remarkable outcomes at age 40:

46%

More likely to stay engaged in schoolwork by age 14

25%

More likely to graduate from high school

20%

More likely to be steadily employed

60%

Less likely to be sentenced to prison or jail

Limits of Traditional Teaching Methods

The Passive Learning Problem:

- Lecture-based instruction creates weak neural connections

- Students memorize content for tests but don’t retain knowledge

- Limited engagement leads to attention and behavior issues

- Content doesn’t transfer between subjects or apply to real-world experience

The Curriculum Replacement Cycle:

- Delivery method matters more than content

- Standardized programs don’t adapt to student needs

- Constant changes demoralize teachers

- Students don’t find generic content meaningful

Addressing Implementation Concerns

Q: “What about test performance?”

A: It’s a pedagogical shift throughout the school day (and year) that often covers curriculum more effectively.6,7 Play-based learners score higher on assessments and understand concepts better than memorizing procedures. 6

Q: “Won’t this require too much prep time?”

A: Play-based learning covers the same content, just in a more dynamic way. Students grasp concepts more quickly, retain knowledge and transfer skills and knowledge from one subject to another–often addressing goals in multiple subjects simultaneously.

Q: “Do teachers need extensive retraining?”

A: Once teachers understand what play-based learning is and why it works, they can begin making small changes to existing lessons. Professional development sessions will be helpful to deepen understanding of play-based components and how to effectively use play to improve student outcomes.

Ready to get started?

References

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We Feel, Therefore We Learn: The Relevance of Affective and Social Neuroscience to Education. Mind, Brain, and Education.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226.

- Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933–938.

- Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78(2), 647–663.

- Duncan, G. J., et al. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1428–1446.

- Skene, K., O’Farrelly, C. M., Byrne, E. M., Kirby, N., Stevens, E. C., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2022). Can guidance during play enhance children’s learning and development in educational contexts? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Development, 93(4), 1162–1180.

- Zosh, J. M., Hopkins, E. J., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Solis, S. L., & Whitebread, D. (2017). Learning through play: a review of the evidence. The LEGO Foundation.

- Schweinhart, L. J., Montie, J., Xiang, Z., Barnett, W. S., Belfield, C. R., & Nores, M. (2005). Lifetime effects: The HighScope Perry Preschool study through age 40. Ypsilanti, MI: HighScope Press.

- Dubinsky, J. M., & Hamid, A. A. (2024). The neuroscience of active learning and direct instruction. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 163.

- Goldberg, H. (2022). Growing Brains, Nurturing Minds—Neuroscience as an Educational Tool to Support Students’ Development as Life-Long Learners. Brain Sciences, 12(12), 1622.

- Schweinhart, L. J. (2004). The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40: Summary, Conclusions, and Frequently Asked Questions. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.